Written by Michaela Coats, Coastkeeper Education Director

Orange County’s coastline is home to some of Southern California’s last remaining wetlands — one of those being the Upper Newport Bay Ecological Preserve (UNB).

The UNB and its 750+ acres of wetland habitat support diverse terrestrial and marine wildlife, including endangered and threatened species. UNB also happens to be the drainage point of the Newport Bay watershed, which covers 152 square miles of densely urbanized land. This exposes this sensitive estuarine system to near-constant urban runoff and pollution. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) has monitored the health of the bay for decades in order to understand how the ecosystem may be changing due to human impacts and other environmental changes.

One of the ways CDFW tracks the health of the bay is through Marine Life Inventories (MLI). Once a month, CDFW brings the community together to participate in this ongoing conservation effort at the Back Bay Science Center (BBSC). Participants rotate through a series of stations that collectively add to long-term data sets. These stations include:

- Bottom trawl, which surveys benthic (a.k.a. bottom) dwelling species living in the channel

- Water quality and mud sampling, which surveys benthic invertebrates living in the mudflats

- Beach seine, which surveys species living near the shoreline

Click here to participate in a Marine Life Inventory!

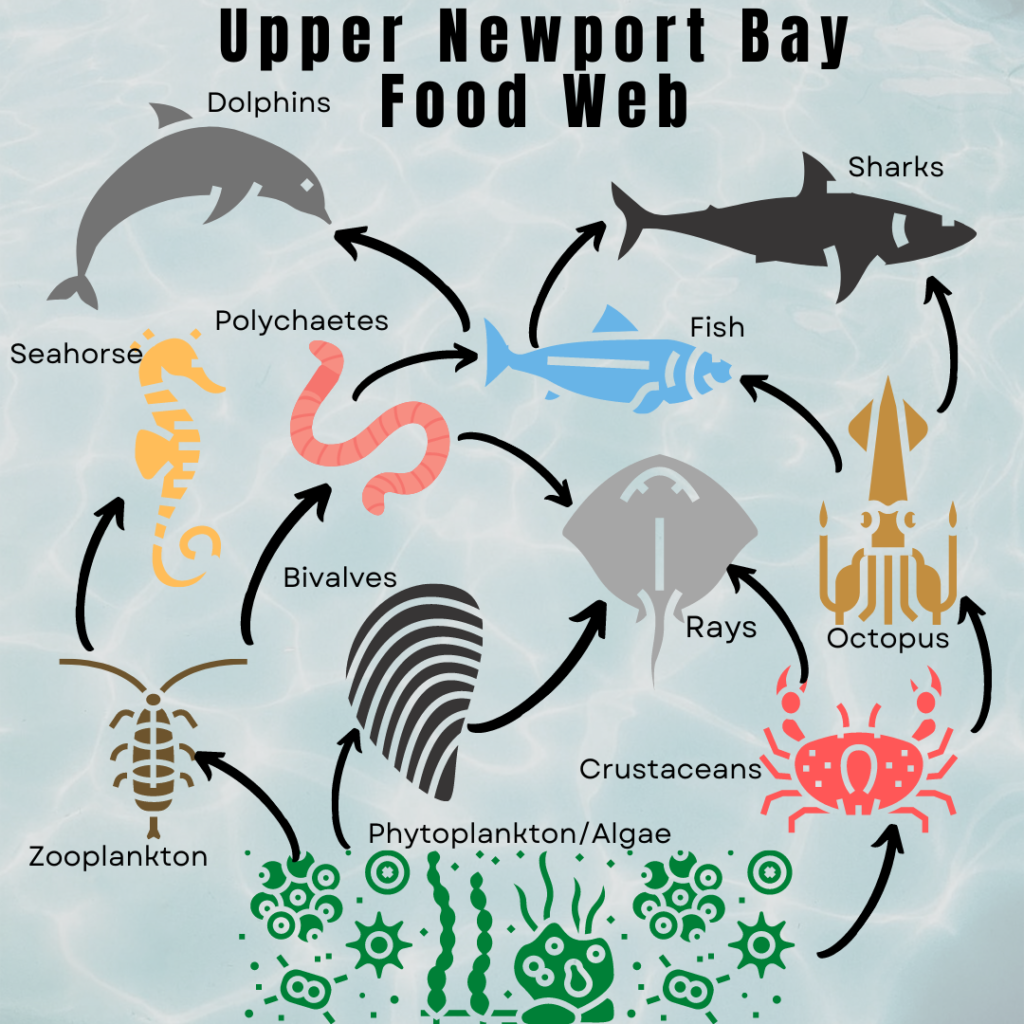

This combination of collection methods aims to paint a picture of the health of the trophic levels, or the different positions within a food web, within UNB. The estuarine food web is densely interconnected, which means that changes to one level can have impacts on those around them. When a trophic level is suppressed or unregulated, it has reciprocal effects on the levels below or above it; this is called a trophic cascade. A popular case study example of this phenomenon is the relationship between sea otters, urchins, and kelp.

The excessive hunting of sea otters to near extinction in the 20th century led to a boom in sea urchin populations since they were no longer being regulated by predation. This, in turn, led to a collapse of kelp forests as they were being over-grazed by the urchins.

Author’s note: This food web diagram is simplified and non-comprehensive.

No two MLIs are like the other; each month offers its own unique surprise. Some common species found are round stingrays, halibut, top smelt, brittle stars, polychaetes, and (invasive) mussels. If we are lucky, we may find a two-spot octopus, navanax, or the rarest find of them all — a seahorse! Sadly, we also never fail to find trash — from bottle caps to shopping carts — amongst our targeted wildlife.

Coastkeeper believes that for people to be stewards of their environment, they have to first connect with it. By participating in MLIs, the BBSC offers a unique experience to connect with the UNB ecosystem in a way otherwise inaccessible.

Coastkeeper is proud to be a long-standing partner of CDFW by running the mud sampling and water quality station at MLIs, as well as contributing to the BBSC’s mission by bringing students to the facility for field trips to experience the diversity of UNB.